In May of 1903, a man by the name of William West, recently convicted of some crime or other, arrived at the Federal Correctional Institute in Leavenworth, Kansas for processing. As the records clerk took the new inmate’s precise measurements, he asked him about the man’s prior murder conviction, at point which a genuinely surprised West insisted he had committed no such heinous crime. The records clerk remained unconvinced, presenting West with a file of a convicted murderer named William West that included his precise measurements and a picture identical to himself.

That a convict might lie about his past crimes didn’t surprise the clerk, but what did surprise him was that the William West in the file was still serving his sentence, and so couldn’t be the William West standing in front of him.

It turned out that the two men, later presumed to be identical twins separated at birth, possessed identical characteristics when processed with the Bertillon measurement of physical characteristics in common use in the US prison system. Fortunately, the clerk was delighted to discover that the two men did have one distinguishing characteristic: their fingerprints.

And that is the excellent story of how fingerprinting became an important tool of forensic science in the United States. Of course as with most excellent stories in history, this bears the telltale too perfectly symmetrical marks of being not precisely true. It makes for good fiction.

In reality, there are oily smudges looping, arching, and whorling all over the smooth surfaces of history, dating back at least 4,000 years when Hammurabi sealed contracts with a fingertip. Not much more recently, the Chinese used inked prints as unique signatures on contracts, and as early as 200 BC may have been using hand prints left at crime scenes to help crack burglary cases.

It was in the 17th century that European scholars started describing the unique combinations of patterns on the ends of our fingers. Then in 1892, Sir Francis Galton, cousin to Charles Darwin, and originator of the unsavory study of eugenics, published a helpful classification of the patterns of fingerprints. That led to Sir Edward Henry’s development of a practical system of identification that could be used in law enforcement, which he presented to Scotland Yard.

Of course as impressive as this sounds, Mark Twain solved a crime using fingerprinting in his somewhat embellished memoir Life on the Mississippi in 1883, indicating, I think, that it would behoove scientists to pay closer attention to writers because they have all the ideas.

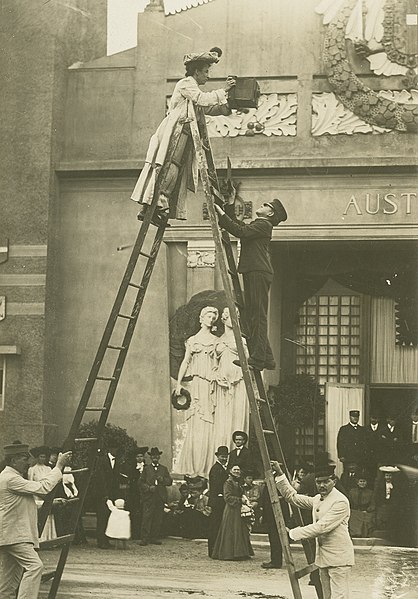

Scotland Yard adopted Henry’s system in 1901, brought it to the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, and presented it to St. Louis police detectives and the general public, including both the fictional amateur sleuth in my novel set at the World’s Fair, as well as the historical M.W. McClaughry, records clerk at the penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas. In September of 1904, fresh from his trip to the fair McClaughry requested that a fingerprinting system be implemented at the prison. It was another one hundred and twenty years before my sleuth put the science to work in my book, Paradise on the Pike.

But even though the story of the two William Wests is somewhat fictional, too, there’s a ring of some truth to it. There were two William Wests at Leavenworth at the same time and they were identical, distinguishable only by their unique fingerprints. They did become a good illustration of the usefulness of the relatively newfangled science of fingerprinting. Still, in reality, the timeline of the story doesn’t quite work out.

When a second William West showed up to be processed, it doesn’t seem that it caused much of a stir at all. It was, however, convenient to have them both there when clerk M.W. McClaughry got excited about this newfangled science that had already been in use in some way for thousands of years. And it sure did make for a good story.