On November 22, 1944 after schedule delays, numerous script rewrites, budget woes, and a leading lady still unhappy with her role, a new Christmas musical debuted on the big screen in St. Louis, the city at the film’s heart.

Despite the mess of getting to that moment, Meet Me in St. Louis enjoyed immediate success, becoming Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s second highest grossing film up to that point, coming in only behind Gone With the Wind. After the premiere, Judy Garland even decided she liked it after all and commented to the producer, “Remind me not to tell you what kinds of pictures to make.”

The screenplay is based on a series of semi-autobiographical short stories by St. Louis native Sally Benson who wrote of an upper middle-class family that lived at 5135 Kensington Avenue during the construction of the 1904 World’s Fair on the grounds of Forest Park in St. Louis.

I confess, I saw the movie for the first time later in life than I should have, having grown up within easy reach of St. Louis. My childhood summers included trips to downtown to watch the Cardinals play at Busch Stadium where the musical’s title song is still played by the organist at every game and the crowd sings along as the words scroll across the jumbotron.

I’ve been many times to the wonderful outdoor Muny theater in Forest Park where the stage adaptation of Meet Me in St. Louis, originally produced in 1989, is performed every few years. I even got engaged in that park on the very grounds of the actual 1904 World’s Fair.

Officially known as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, the Fair is a big deal in St. Louis history. It transformed the city, launching it for about seven months into the center of the world’s attention.

And it’s still a big deal, today. One-hundred and twenty years later the World’s Fair looms large in the community memory carried now by not a single living person who was there to see it, sparking excitement whenever it comes up in conversation, which is kind of weirdly a lot.

It’s especially on everyone’s minds right now because at the end of this month, just in time to celebrate the 120th anniversary of the opening of the Fair, the Missouri History Museum will reveal a newly re-imagined permanent World’s Fair exhibit.

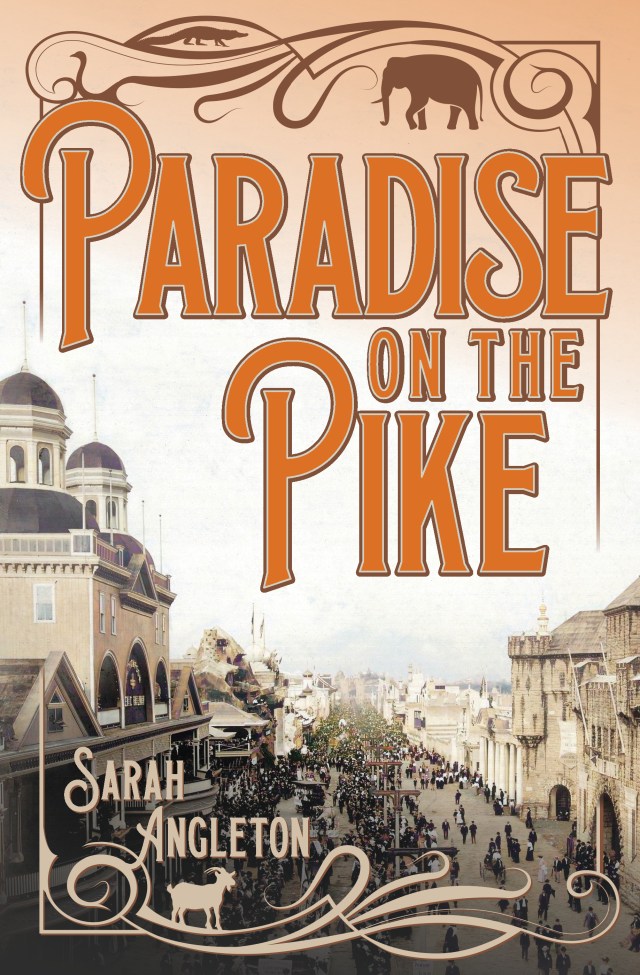

Equally exciting for everyone who either lives in my house or happens to be my mother, is the release of my new historical mystery set on the grounds of the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis.

Paradise on the Pike is available for the first time today. The story takes place in the enchanting world of Hagenbeck’s Zoological Paradise and Trained Animal Circus on the Pike, which is the entertainment strip within the Fair. It’s not a light, sentimental sort of story like Sally Benson’s, but it does contain elephants and lions and a pair of cantankerous goats. It also allowed me, and will hopefully allow you, to spend some time strolling through the Fair, which was almost entirely constructed of temporary buildings meant to disappear.

And maybe that’s why, one hundred and twenty years later, it still takes up space in our imaginations, because we’re a little like six-year-old Tootie at the end of Benson’s stories when the family marvels over the lights and fountains on the fairgrounds and her sister Agnes asks if it’ll ever be torn down.

Tootie emphatically replies, “They’ll never tear it down. It will be like this forever.”

Agnes, relieved, exclaims, “I can’t believe it. Right here where we live. Right here in St. Louis.”

Forest Park retains very few physical reminders of the enormous event that once filled its every corner and held the attention of the world, but in the hearts of the St. Louisans who stroll through the grounds and wish they could have seen those lights shining, it will never be torn down. It’ll be like this forever.

You can find more information about Paradise on the Pike at this link.