It wasn’t until 1976, under the direction of then US president Gerald Ford that Black History Month became an officially designated event in the life of the United States, though versions of it had been recognized in various parts of the country for fifty years by then. Ford hoped that Americans would “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.”

It does raise some controversy, which I can understand somewhat. To designate only one month to the contributions of Black Americans throughout history could be considered a disservice both to Black Americans and to American history itself, which is much better understood when all of its threads are looked at together. I get that argument.

I have, fortunately, seen in my lifetime a noticeable shifting in the way history is taught to incorporate more of the Black voice and I am hopeful that trend will continue, but I also see value in setting aside time to focus on some of the things we still have the tendency to miss.

I will be the first to admit that this blog rarely features history from the Black community. The reason for that is certainly not intentional racial exclusion, but stems rather from the reality that this blog is a place I generally try hard to keep fairly lighthearted, which so much of Black history sadly is not. It’s made up of a great deal of struggle and I have a hard time knowing how to write about that in the same space where I joke about cussing parrots and moon poop.

But today, I do want to take the opportunity to look at the neglected story of an impressive Black man who appears in my most recent novel, White Man’s Graveyard, a book that includes neither cussing parrots nor moon poop, but does wrestle with some complicated and racially charged American history.

Born free in Rhode Island in July of 1801, Reverend George S. Brown was a skilled stone mason and a powerful preacher. Rumor has it he also played the bagpipe, but I won’t hold that against him. Brown traced his conversion to 1827, when, emerging from a part of his life he referred to as his years of carousing, he felt called to the Methodist Episcopal Church where he soon became a licensed preacher.

And boy did he preach. At one point while he attended seminary, he was told he couldn’t preach because it proved too distracting from his studies. He did it anyway. And it seems that people listened. His diary is filled with references to sermon topics and scripture passages, to congregations and conversions, and what is amazing for the time is that he was as likely to preach, and be well received, in white churches as he was in Black.

In fact, the only Methodist Episcopal Church to which he was ever officially appointed lead pastor was in Wolcott, Vermont, where in the 1850s, he ministered to a white congregation and even led them through a building campaign.

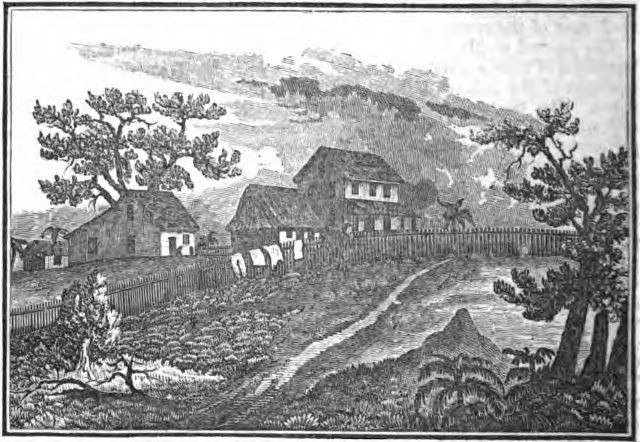

Before that, however, he served as a missionary to Liberia. That’s where I first encountered George Brown, encouraging purses to open and prayers to flow for the outreach opportunities presented by the colonization movement which sought to firmly establish an African colony for former American slaves.

George Brown was arguably the most effective Christian missionary to ever serve in the colony of Liberia. He established a mission post east of Monrovia called Heddington where he and his church of indigenous Africans withstood a brutal attack from slavers, and sought opportunities to reach further into the interior of the continent with the gospel message.

Brown also did not shy away from standing up to his white colleagues, including physician Sylvanus Goheen (one of the main protagonists in my novel) and mission superintendent John Seys, whose legal struggles with the colonial government seemed to Brown a terrible distraction from the mission. His refusal to align with a side, both of which he saw as wrong for various reasons, led to legal trouble of his own when Seys later attempted to block him from full ordination in the United States.

That’s where the story becomes sad and familiar because of course, the word of a white man outweighed the claims of even a well-respected and free Black man in 1840s America. Thankfully, George Brown persevered and eventually won the court battle.

Reverend Brown is in my book because he was an integral part of the historical story on which it is based. In my earliest notes, he even provides one of the voices through which the story is told, but in the end, I didn’t think I could do him justice. Maybe someday another author will pick up his story and run with it. I hope so, because he strikes me as a man of deep conviction and unwavering integrity, an American well worth learning about this month and in the other months as well.

It’s true he never left bags of poop on the moon and if he owned a parrot that swore like a sailor, I never found any record of it. I do wish I had discovered more than a fleeting reference to his bagpipes, though, because I find that stories about bagpipes are often genuinely hilarious.