In 1931, Michigan-born illustrator Haddon Sundblom was approached by the Coca-Cola Company to reinvent the image of Santa Claus. The artist had a lot to work with. The legend which had begun with the generosity of a 4th-century bishop was Americanized by Washington Irving in 1809.

In 1823, thanks to the poetry of Clement Moore (maybe), he became a jolly elfish figure with magical flying reindeer. During the American Civil War, artist Thomas Nash gave St. Nicholas his more familiar name. Santa Claus became an enthusiastic Union supporter dressed in fur from head to toe.

American artists Rockwell, Wyeth, and Leyendecker captured the essence of Santa Claus in the early 20th-century. The jolly fat man received a fur-trimmed stocking cap, wide black belt, black boots, and a large bag of toys. This is also when red and white became his undisputed favorite colors.

By the time Sundblom got hold of him, Santa already resembled a Coke can in the American imagination. But Santa was still elfish, stern, and a little bit too much like a random fat guy in a funny suit. Evidently, that didn’t make people want to run out and drink Coca-Cola.

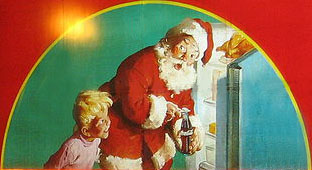

Sundblom solved the problem by recruiting his neighbor, a fat, jolly salesman, to model for him. The result was a magical looking image of a warm and friendly man people the world over began to identify with. For thirty years, Sundblom breathed life into his Santa. He played with toys, relaxed by the fire, and pilfered the Christmas feast from the refrigerator.

But it isn’t exactly true. What they did was standardize Santa as a fat kleptomaniac with a friendly face and a raging Coke addiction. And Christmas has been all the jollier ever since.

My kiddos have outgrown their Santa years, and thankfully we never got into that creeptastic Elf on a Shelf thing. But they appreciate the magic of the legend, and they’ll have a hard time getting to sleep on Christmas Eve. Because our stockings are still hung by the chimney with care, and my boys know St. Nicholas soon will be there.

He’ll be jolly-ish as he assembles surprises late into the night (maybe we could use an elf on our shelf). He’ll drink the Coke left for him on the hearth because he’ll need the caffeine. And before he stumbles bleary-eyed into bed, he might even raid the fridge.

![First president of Turkey, with his modern Panama hat. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://sarah-angleton.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/ataturk-hatreform.jpg?w=287&h=300)

![Six Hours. Hooked up to this. That better have been a really good perm. By Stillwaterising (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://sarah-angleton.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/permanent-wave.jpg?w=225&h=300)

![Admiral Nelson had previously lost his right arm in battle. It is not clear in which liquor barrel it was stashed. Oil on canvas by Lemuel Francis Abbott [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://sarah-angleton.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/horationelson1.jpg?w=249&h=300)

![Thanks to Isabella Mandl, et. al., recipients of the 2011 Ig Nobel Prize for Physiology, we now know that red-footed tortoises do not experience contagious yawning. And I know we were all wondering. By Ltshears (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://sarah-angleton.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/red_footed_tortoise_001.jpg?w=300&h=256)