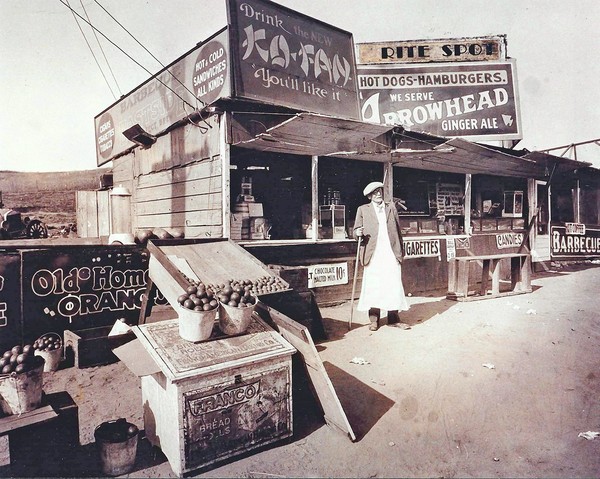

In 1924, while working at his family’s roadside sandwich stand, The Rite Spot, in Pasadena on a part of the famous Route 66, 16-year-old Lionel Sternberger made history when he placed the first slice of cheese ever to grace the top of a hamburger patty. Probably.

How exactly it happened is a little unclear. One story suggests that Lionel burned the patty and so he threw on the slice of cheese to cover up his mistake. A slightly less dramatic theory is that a clever, uncredited, customer asked for cheese on their burger and Lionel simply obliged.

But another entirely different tale of the invention of the cheeseburger comes from Kansas City, where a man named Charles Kaelin claimed in 1934 to have had the first genius idea to add tang to a hamburger by adding cheese, just a year before the owner of Denver’s Humpty Dumpty Drive-In first trademarked the word cheeseburger.

There are probably other origin stories as well, and we could certainly debate about them, and produce all kinds of memes and reels and righteously angry and potentially insensitive social media tirades, though somehow I doubt we’d get anywhere productive. I’d rather take today, National Cheesburger Day here in the US, to appreciate and celebrate what we have in common: this fine sandwich we all know and love.

Well, most of us probably love at least some version of it. What precisely goes on a cheeseburger is not always the same from burger stand to burger stand or from backyard grill to backyard grill.

We can all pretty much agree that it needs to include some sort of beef patty. Unless of course you don’t eat beef and prefer something like bison or venison or even turkey. Or I suppose you could be vegetarian and stick to a plant-based patty or replace it all together with a big beefy portibello mushroom, which I guess still counts.

A bun, too, is standard, either with sesame seeds or without, smeared with a little butter and toasted, or not. Maybe a gluten free bun is your jam or no bun at all. Some people, though surely not anyone I’d want to know, replace the bun with a couple large pieces of lettuce.

There’s also the question of what kind of cheese you use. The traditionalist might go with a cheddar or a melty American, but Pepper Jack can pack a nice punch or blue cheese, an odd funk, in case you’re into that sort of thing. If you’re a little pretentious, a Swiss or smoky Gouda could work, and then there are the vegans among us that I guess have to settle for some sort of not-a-cheese product.

And then we hit the question of toppings. Ketchup is pretty standard, unless you’re dead set against it. Mayonnaise is a contender, too, for those with no taste buds. Steak sauce might work, again, for the unapologetically pretentious. The indulgent might like to add bacon to theirs, and the vegetable obsessed will insist on lettuce, tomato, and pickles, while people who completely hate themselves might even consider raw onion a defensible choice.

With all of these certainly not exhaustive options, maybe the best thing to do would be to avoid confusion and standardize the cheeseburger. And if we do that, then we could make sure we are providing the ultimate cheeseburger experience to all people, regardless of their individual backgrounds and ill-informed biases.

We could use only the very best ingredients, too, and perhaps limit the consumption of cheeseburgers so that people don’t stress the healthcare system with their poor choices or shape the supply chain in a way that we suspect might overburden either the environment or the market.

Yes, it’s true that at first we could get some push back. Some cheeseburger stands and backyard cookouts may initially fail to comply, and will likely use hateful rhetoric to insist that they have a right to prepare and eat cheeseburgers the way they want. If these deplorable enemies of culinary taste get a chance they might even spew their venom in public debates in which they claim it could even be a good and useful thing to consider alternative ways of preparing cheeseburgers.

I believe, however, that if the truly good and hungry people of this nation fight hard enough and take to the streets to protest the non-compliant businesses and backyards, maybe squish up a few buns, torch a couple of grills, and throw a few ketchup bottles, we can silence the opposition. I bet. You know, for the good of all.

But of course, I jest.

In truth, I feel that if you want to ruin your otherwise perfectly delicious cheeseburger with a hunk of raw onion, you should be free to do so. We can even still be friends, provided you brush your teeth before standing close enough to, say, engage with me in a heated political debate. If, however, you try to put a hunk of raw onion on my cheeseburger, be forewarned that I just may say something hurtful on social media that I’ll probably regret and have to try to apologize for later.