In 1882, owner of the Rock Island and Milan Steam and Horse Railway Company, Bailey Davenport took on a new business venture to drive more business. What he created was Watchtower Park, a leisure destination at the end of the line on the bluffs overlooking the Rock River at Rock Island, Illinois.

This recreational park, admission to which was included with the price of a trolley ticket, opened with groomed hiking trails, a grand pavilion with picnic tables, and what Davenport advertised as a healing spring. Eventually, it would expand to include live theater, vaudeville, tennis courts, and billiards tables.

But the biggest attraction, built in 1884 by J. P. Newburg, was a five hundred foot greased wooden track built into a hill down which a wide flat-bottomed boat zoom toward the river where it created a satisfying splash and glided across the surface of the water. An attendant then used a pulley system to drag the boat back up the hill for another go.

Watchtowers “Shoot the Chute” ride was the first of its kind, but the design quickly took off, becoming a frequent feature of amusement parks throughout the United States and the world. It’s probably no surprise then that a Shoot the Chute ride popped up in 1904 in the entertainment section, known as the Pike, on the grounds of the World’s Fair in St. Louis.

What might be more surprising is that there were actually two such rides on the Pike—one for the fairgoers, and one for the elephants at Hagenbeck’s Zoological Paradise and Trained Animal Circus. And just as a visitor standing nearby the Shoot the Chute could expect to enjoy a cool splash on a hot, sticky St. Louis summer day, a visitor to Hagenbeck’s could get showered by the kerplunk of an 8,000 pound pachyderm.

The elephant slide sure did make a splash, and appears frequently as a highlight in fairgoer written accounts. One biographer of Hagenbeck elephant trainer Reuben Castang even recounts a shared story in which Castang took an accidental plunge with the giant animals, and lived to play it off as if it had been a planned stunt.

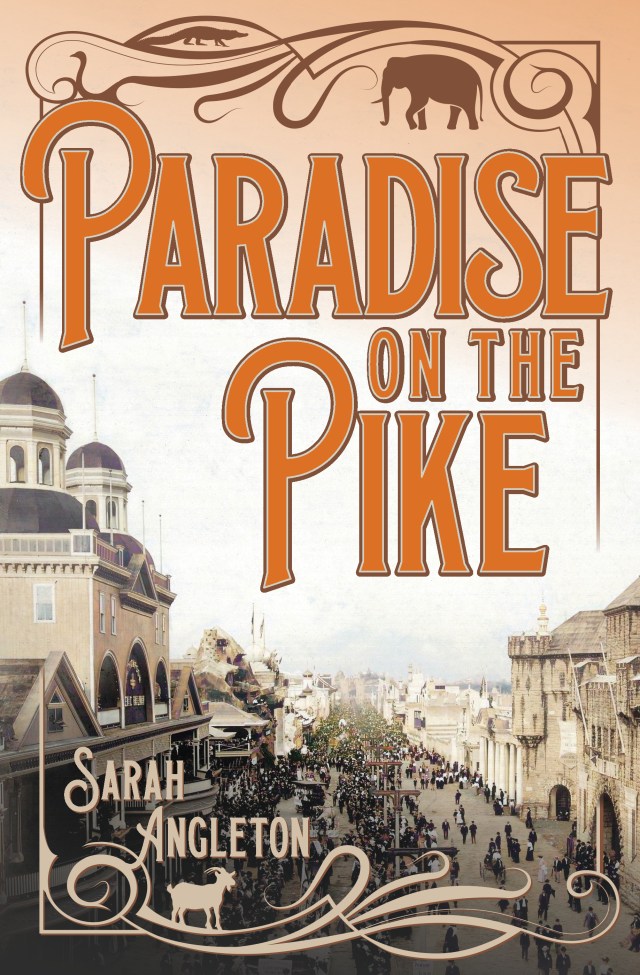

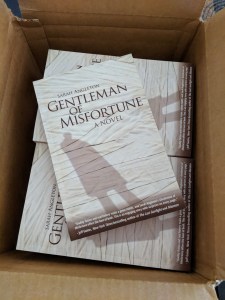

A fictionalized version of this scene appears in my new historical mystery, Paradise on the Pike, which came sliding onto the market this past week. With any luck, and with a lot of help from wonderful people spreading the word and building the buzz, it’s making a big enough splash that readers will notice and take a chance on it.

Hagenbeck’s Zoological Paradise and Trained Animal Circus is central to the novel, which is populated by elephants and many other animals that were fun characters to write. And of course sometimes when researching, you come across something that you just can’t leave out. Because everyone loves a good Shoot the Chute ride and some stories just make a big splash.

If you’d like to read more about the real Hagenbeck elephant antics that appear in the book, check out my guest post featured by writer and very gracious host Roberta Eaton Cheadle on her blog Roberta Writes.