In the late sixteenth century French Jesuits brought the first apple seeds to America and by the time missionary John Chapman became the legendary Johnny Appleseed in the late eighteenth century, the fruits were already a pretty important part of American culture. Apple pies were on their way to becoming as American as they were ever likely to get, and the hard cider was flowing.

Then came the increasing influence of German immigrants who brought with them an enthusiasm for beer. Barley grew well in the US. It was a quicker and cheaper crop, too, and recovered more easily when it occasionally fell victim to the whim of the temperance movement. Apple trees began to decline, beer surged, and apple cider became the drink of the backward-thinking country bumpkin.

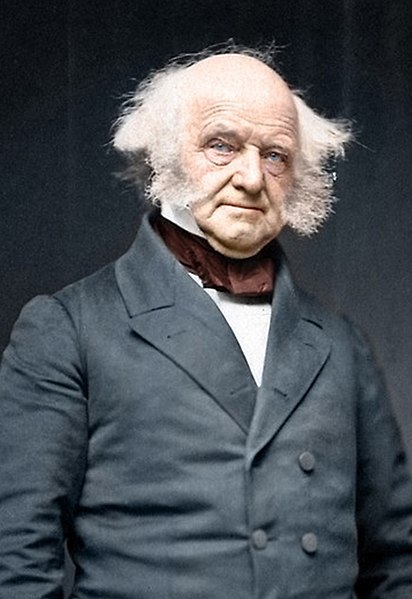

That’s probably why, during the presidential campaign season of 1840, a Democratic newspaper insulted the Whig challenger to the Democrat incumbent Martin Van Buren by stating that you could “give [William Harrison] a barrel of hard cider. . .and he will sit out the remainder of his days in a log cabin by the side of his ‘sea coal’ fire, and study moral philosophy.”

The insult turned out to be a pretty big misstep because the US was in the midst of an economic depression that had occurred under the watch and policies of Van Buren and his Democrat predecessor Andrew Jackson. People were stressed and were perhaps feeling nostalgic for better days, even longing for a return of the hard cider they’d previously dismissed.

Harrison, who’d been raised as a wealthy and well educated Virginian with a pedigree every bit as hoity-toity as Van Buren’s, embraced hard cider which paired well with his reputation as a western hero of the War of 1812. Yes, it was maybe a little disingenuous, but when life hands you apples, you make hard cider.

That’s what we’ve decided to do this fall at the Angleton house. Shortly after moving into our current suburban home more than ten years ago, we planted three apple trees, of different varieties. One started producing a pretty good harvest the first year or two. The others took a little longer, but now all three are going strong and we are drowning in apples.

This is not a terrible problem to have. We share a lot of them with friends, family, neighbors, and food banks. With the rest, we get creative. Over the years we have canned applesauce, made apple butter, baked pies and cakes and muffins and doughnuts. Our apples have been the star of salads, hors d’oeuvres, main dishes, and snacks. The only thing we hadn’t done was make cider because we didn’t think we had the right kind of apples to make it work.

But then we found a stovetop recipe that isn’t too picky and it turned out really well. The next logical step then was to try our hand at fermenting it, because it felt like just the kind of thing nostalgic Americans should do.

Turns out it’s not that difficult. It does require some precision and care and a bit of patience. Our first batch isn’t quite through its initial fermentation yet, but as best as we can judge from all our recently obtained YouTube expertise, it’s coming along nicely so far.

Hard cider worked out for Harrison, too. He defeated Van Buren in an electoral college landslide, becoming the oldest person ever elected to the office (a record that has definitely been broken since) as well as the first to lay claim to a campaign slogan.

His success didn’t last, however, because after delivering the longest ever inaugural address (a record he does still hold), in the cold, without even stopping to take to his bed, he developed pneumonia and just a month later, became the first US president to die in office, after the shortest term ever served.

I do hope we have better luck with our hard cider.