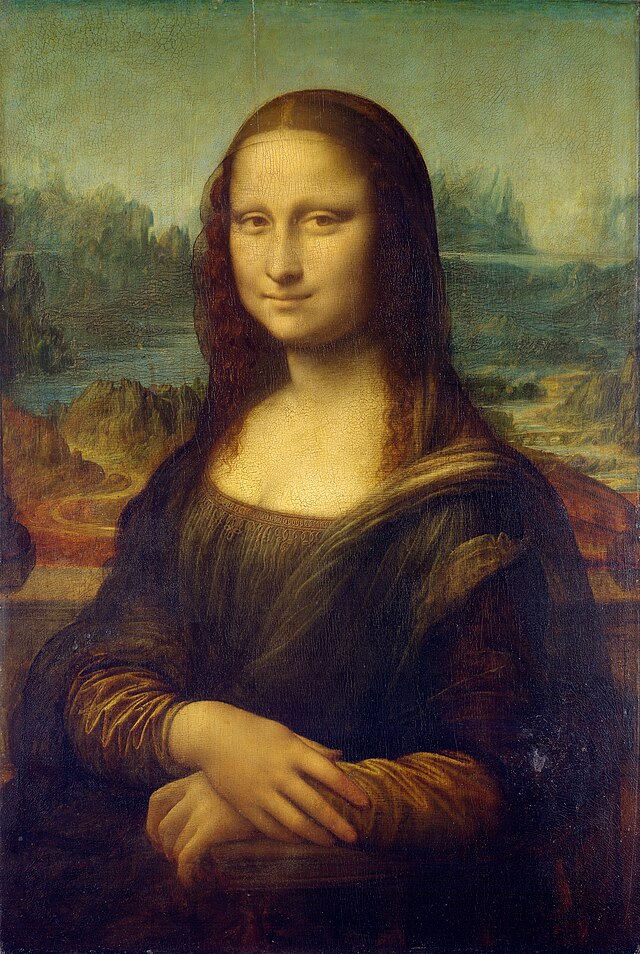

On August 22, 1911, artist Louis Béroud intended to spend his day at the Louvre, working his way through mimicking the paintings in one of its many galleries. He’d chosen Salon Carré, the room in which a small 16th century painting by Italian Renaissance polymath Leonardo da Vinci smirked from behind glass between Antonio da Correggio’s Mystical Marriage and Titian’s Allegory of Alfonso d’Avalos.

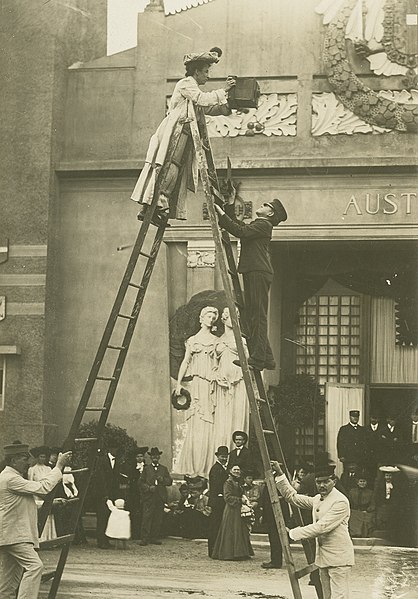

When he found an empty spot where the Mona Lisa had been on display for more than a century, he didn’t initially think much of it. At the time, there was an ongoing project to photograph many of the paintings in the Louvre, and several had been removed from their display locations temporarily to capture better lighting on the roof.

The portrait had been the focus of critical attention in the art world for about fifty years at that point, as an excellent representative of Renaissance oil paintings, but outside that circle, the world hadn’t really given the Mona Lisa much thought.

That changed the moment Louis Béroud thought to ask one of the security guards when the painting might be returned, and the guard discovered that the painting hadn’t been taken for photographing at all. It was missing.

A thorough search of the museum didn’t turn up the painting, nor did nearly two years of investigation. The story became a fascinating true crime mystery and made the Mona Lisa, with its curious half smile and uncertainly identified subject, one of the most famous paintings in the world. It also made the empty spot where it had hung the most highly visited blank gallery wall in the world.

It’s that part of the story that I find most interesting, that people came in droves to stare at a vacant bit of wall. Of course, I don’t know why they all came. Maybe they were hoping to find clues or at least understand the circumstances of the crime a little better by putting themselves in the space. Maybe like the Instagrammers of today, people just wanted to seem interesting at parties because they’d taken time to be there, and obviously they’d always known that the Mona Lisa was an important work of art.

But lately, as I see the social media posts of so many grieving friends sending their newly grown up kids out into the world to college, or the military, or apparently in one lucky young man’s case, a gap year European tour, I tend to imagine that the crowds came to the Louvre as an expression of grief that they couldn’t quite make sense of and couldn’t quite shake off.

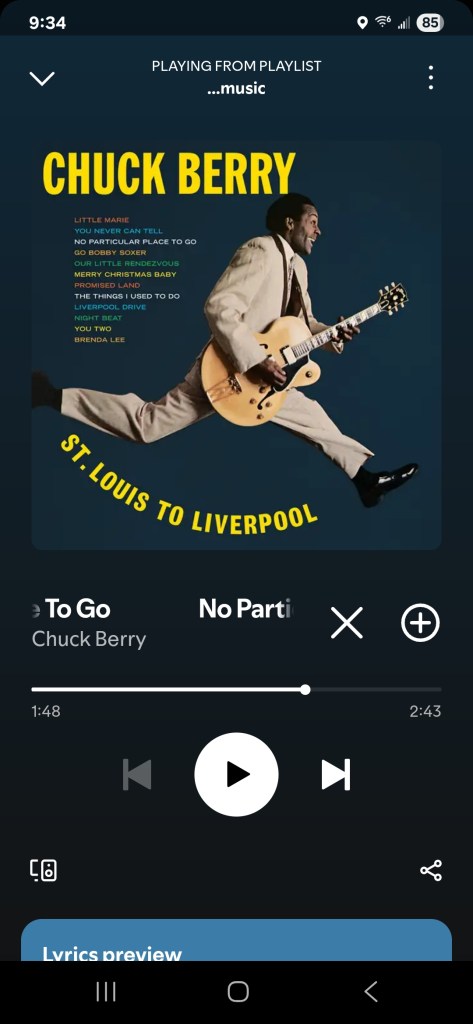

I imagine all those parents are catching glimpses of, and maybe even intentionally visiting, bedrooms once occupied by the children they never fully understood until now just how much they would miss. For me, it’s not the room so much, though it is sad and empty, but the Spotify list that I can’t stop listening to because it makes it sound like my youngest son is still at home.

I realize this is not a perfect analogy of course, because at least I hope every parent who’s watching a son or daughter leave the nest, already knows their kid is a work of art that fills an important space in the history of the world.

Thankfully for most, even though their grief is very real, their young adult children will eventually return home, at least to visit. Mona Lisa did finally turn up again and wound its way back to the Louvre. It had been stolen on August 21st, the day before Louis Béroud noticed it was gone, and a day when the museum was closed.

Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian man who had been employed at the museum, and helped install the glass that protected the painting, had walked out the door with it. The Mona Lisa’s almost immediate burst of fame had made it impossible for him to do anything with it and only when he attempted to fence the work two years later was he finally found out and arrested.

Today, Da Vinci’s kind of cheeky portrait is the most visited piece of art in the entire world. Because when you get the chance to miss something, that’s when you truly understand how special the time you spend with it really is.